News

15 April 2021The Netherlands’ need for a nature-based future

In a world facing climate change and biodiversity loss, nature-based solutions have a crucial role to play, says Tim van Hattum, one of the authors of a 100 year vision for the Netherlands.

“Climate change and biodiversity loss are the biggest challenges of the 21st century,” says Tim van Hattum, Programme Leader Green Climate Solutions at Wageningen University & Research (WUR), a member of the Netherlands Water Partnership.

At a basic level, it is clear what needs to be done, such as targeting zero carbon emissions, adapting to the impacts of climate change that are already with us, and restoring biodiversity. The question is how to do these. “We have to find an integrated way,” Van Hattum continues, adding that the current pandemic demonstrates our tendency to focus on problems in the short term. “We really need a long-term perspective and a long-term strategy to solve these issues.” He believes that many approaches will have a part to play in the transformation ahead. One example is technology such as electric vehicles being part of the energy transition. “In my view, nature-based solutions are a big part of the solution,” he adds. “They need much more attention.”

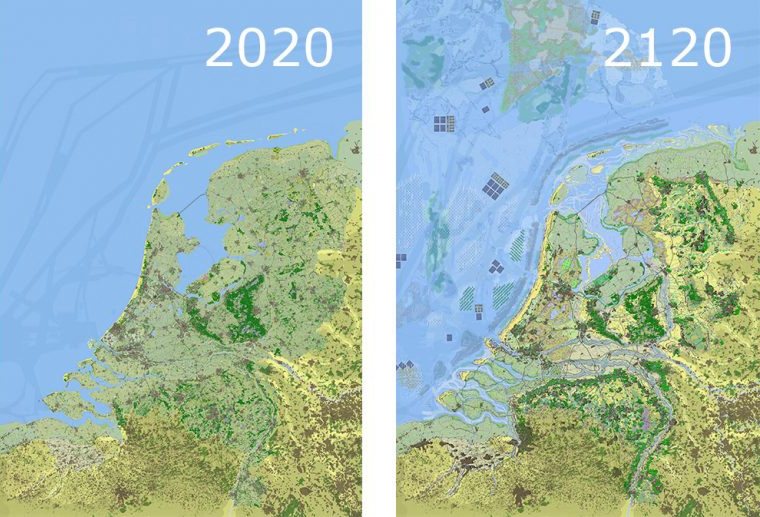

This need for a long-term perspective and greater attention being paid to nature-based solutions were behind a vision set out by WUR at the end of 2019 in a document entitled ‘A nature-based future for the Netherlands in 2120’.

“We wanted to show that if we implement nature-based solutions at a massive scale, we can make our country even more attractive to live in,” he says. People tend to either think in the short term or, if they do look ahead, they are very concerned about the future in terms of climate change and biodiversity loss. “The message we wanted to bring across was that we can turn them into an opportunity,” he adds.

Guiding principles

“We asked ourselves, if we redesign the Netherlands and make it future-proof, what kind of guiding principles do we need?” says Van Hattum. “The first principle we came up with is that we have to work with nature.”

The vision included: using the country’s best soils for plant-based food production; doubling the number of trees to increase carbon storage; and, using a reduced amount of livestock as part of a circular food system.

Water also had a big part to play in the vision. “The Dutch have been fighting water for centuries, but we are also starting to realise that we cannot keep fighting water,” says Van Hattum. “We created much more space for water in the vision – we gave our rivers much more space to flow,” he adds.

The changes around water went further than this; they built on a new perspective. “Our water management is based on getting rid of water as soon as possible,” says Van Hattum. He explains that the last three years have been very dry, and that climate change means that periods of drought will become more frequent in the future. “We have to rethink our water system again and actually retain all the water we have in the system. Our landscapes should act like sponges, retaining water so that we can use it in periods of drought while preventing floods,” he adds.

This is not just about rural areas. “Our cities will become much greener, and we will use green to cool them and make them act as sponges that accommodate and retain the rainwater,” says Van Hattum.

Applying nature-based approaches

The vision generated a lot of interest when it was released. “It received a lot of attention – everybody was talking about the map, because we visualised the future. We were very surprised by all the attention,” says Van Hattum. “We also learnt that there is a huge need in society for a hopeful future perspective.”

If we look forward to a nature-based approach, using natural areas to turn the landscape into sponges is a big change, Van Hattum explains. “It is really a major shift in mindset,” he says.

“We are learning how to do this through pilot projects, but we have to upscale these pilot projects,” he says. “We have to upscale them faster than we thought,” he adds. “We expected to have these dry years in 2050, but they are coming earlier and earlier.”

There is still much work to do if nature-based solutions are to be used more widely, especially given that every place in the world is different. “Nature-based solutions and nature-based thinking is quite new,” says Van Hattum. This means there is a need for design standards, for example. “There is still a high need for knowledge development about nature-based solutions, the costs, the effectiveness, and the benefits,” he says, commenting that the last point is particularly needed to support a business case for implementation.

Beyond the nature-based solutions themselves, there is a wider need to turn the vision into an action plan. The pandemic has clearly made this difficult. “In the meantime, we have talked to hundreds of people, and we are working on the next steps,” says Van Hattum. “Another huge need in the Netherlands is for a Ministry of Spatial Planning that will take the lead in this discussion,” he adds.

Even without one, Van Hattum sees that the potential for nature-based solutions is clear, especially given their ability to address both climate change and biodiversity loss. “We know that these are the biggest challenges for the 21st century – there is no doubt about that, and nature-based solutions are a really good step forward.”

He is also clear about the value of developing a vision, such as the one prepared for the Netherlands. “To be honest, I think every country in the world should develop a vision like this, to show the way we can go, and to show that nature-based thinking is inspiring so many people and solving so many problems at the same time.”

Featured NWP members: Wageningen University, Alterra